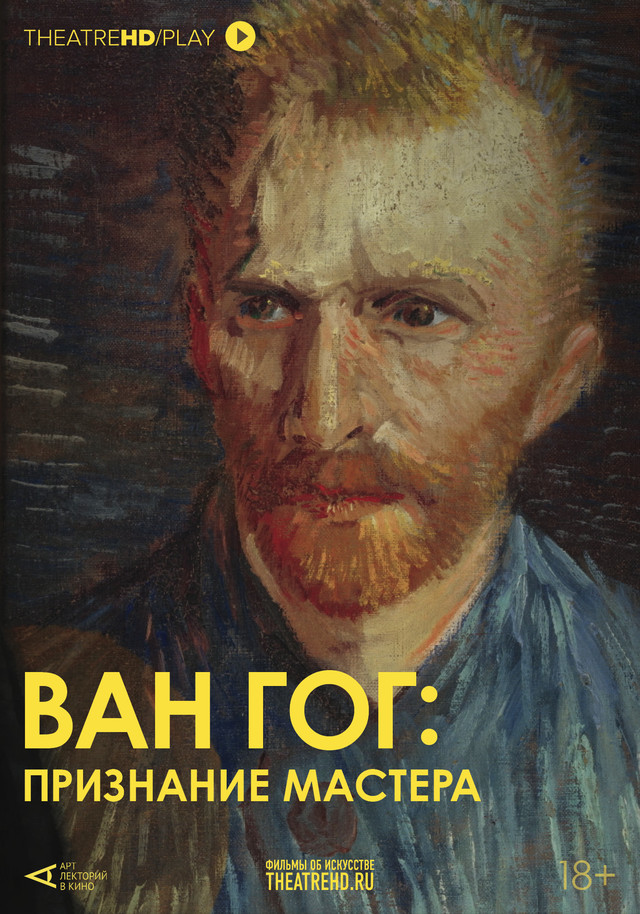

Van Gogh, deux mois et une éternité

Director Anne Richard

Logline:

This film invites us to rediscover the work of Vincent Van Gogh through the character of Johanna Bonger Van Gogh, hissister-in-law and inheritor of his estate. Although she knew him only for the last two months of his life, she devoted her life to making his painting known to the world. By following her painstaking efforts to understand his art and make it known to critics and dealers, we see Van Gogh's genius in an unprecedented and profoundly human perspective.

Director's Statement:

Van Gogh'sfinal two months, which he spent in Auvers-sur-Oise, were one of the most prolific periodsin hislife. He painted more than 70 canvases at a frenetic pace, sometimes up to three a day. Striking masterpieces in thick strokes and contrasting colours, numerous Champs de Blé, Les Maisons à Gré, Le Jardin du Docteur Gachet, and ghost-like portraits: Docteur Gachet, Adeline Ravoux or Melle Gachet au Piano. It is also one of the most analyzed and commented-upon periods of his life, which ended in July when he shot himself in the chest,sealing hisfate as a doomed artist and feeding the legend of the mad painter that has generally taken hold ever since.

There is something that appeals to me about this fateful period in Auvers-sur-Oise and in the years that followed, unencumbered by subsequent debate. First, foremost and closest to the heart of the enigma, it concerns a woman who was a privileged witness to Vincent’s last months and who is none other than his own sister-in-law, Theo’s wife Johanna. She met Vincent just three times in his life: in Paris before he went to Auvers and then on two other occasions during the summer. She is nevertheless a central figure in the Van Gogh trio. She crossed paths with all the other protagonists who were close to him atthe time, such as Dr Gachet in Auvers. She saw friends of Vincent and Theo, such as the painters Émile 4 Bernard, Camille Pissarro, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the critic Albert Aurier, come and go in her apartment.

Above all, afterthe death of the two brothers, Vincent in July 1890 and Theo in January 1891, it was she who had the whole of Vincent's work before her eyes, even though it was considered almost worthless: it wasshe who took on the task of interpreting it, assembling it, curating it and bringing it to the attention of the critics and then the public. Widowed and a single mother at 27, she took up the study of art, almost in spite of herself, as it was neither her training nor her destiny. Despite the pain of her bereavement, she learned to recognise artists’ techniques with form and colour, and above all else to “love” Vincent, becoming his main posthumous champion.

In her notebooks, she hides nothing of her sadness, her difficulties in managing, or her difficulties in convincing her close friendsin the art world of Van Gogh’s genius. Naturally she makes a few blunders in naïvely asserting her convictions in a traditional world in which it would have been hard to imagine a widow having as much skill as her late husband. Sometimes she despairs, but never gives up. At night, when her child is asleep, she opens the voluminous correspondence between Theo and his brother, which he kept in a writing-desk and read over and over again before his death. She plunges in thinking she would rediscover Theo, the love of her life; instead she finds Vincent, the artist.

Her intuitive genius lay in understanding that the keys to Vincent’s work were to be found in these letters. After a few failed attemptsto convince the critics, Johanna began to charm them by reading passages from the correspondence. She managed to convince well-known friends and neighbours, including the painter Jan Veth and then the critic Roland Holst, who had initially been irritated by herincompetence. They changed their minds afterreading the letters and then helped her to mount a first exhibition in Amsterdam in 1892. On the strength of her experience, she then organized the great exhibition of 1905 at her own expense, the largest retrospective on Van Gogh in the history of art, which brought together some 500 works. Progressively, almost all over the world, she raised the price of Van Gogh’s paintings as well as interest in the artist: he was rediscovered as a genius who had been misunderstood during his lifetime.

So, thanks to Johanna, I can offer a new film on Van Gogh. As I see it, Johanna appears to be a key to the Van Gogh enigma: it was she — even, of course, if she was well-connected and supported — who was able to identify in Vincent what made him unique as an artist and to ensure his recognition. One could say that this is a feminine view of the famous artist that has never existed before, or that it is a kind of homage to a woman forgotten by history, but these are not the only reasons that legitimise the desire for this documentary today. To revisit Van Gogh’s biography and work through Johanna’s eyes and words is to tell the story of painting from the perspective of one who is not an art expert: to develop a naïve initial view and then a more sophisticated one, to embrace a form of apprenticeship of the vision by passing from letters to paintings and then from paintings to letters. It means finding Vincent through Johanna’s memories, through his relationship with his brother and the works he sent him, and finally through his own words: those of a man struggling with his demons and his art. In this way, perhaps, we get to (re)discover (the genius of) Vincent Van Gogh.

Synopsis:

The film is conceived as an intrigue around the interpretation of Van Gogh’s work. The narrative follows the last days of Vincent Van Gogh — two months — and his legacy. The plot is set out from the beginning of the film by focusing on the character of Johanna. From the outset, she is alone as Theo’s widow, surrounded by Vincent’s paintings and the letters between the two brothers. From this situation, I build a scenario that plays with flashbacks, a natural element in a period of mourning. With no idea of what to do but take over her husband’s mission, calling up her memories, distraught when she is advised to burn the paintings as “the work of a madman”, Johanna takes the letters from the famous writing-desk. The more she reads, the more memories of Vincent, through Theo, come back to her. I imagine her looking at the paintings around her, contemplating them, perhaps even lost in speculation about his troubled personality, his incomparable talents, his energy in producing so many paintings, or about what might have happened at the end of his life. From the paintings,she turnsto words, to letters. There she finds a new key, new clues, new memories. She returns to the paintings. Slowly, Vincent the artist is revealed to her, and she becomes his ardent champion for the rest of her life. I imagine this scene being played out in the film in the villa in Bussum, then in the house in Amsterdam, where again and again she positions Vincent’s paintings more or less as they had been in the conjugal apartment in Pigalle. This scene emphasizesJohanna’s concerns about the immensity of Vincent’s œuvre, which is always present, confronting her.

Meanwhile, the film progresses through two narrative threads in two different time spaces:

• Vincent at work: from the moment he leaves the asylum in Saint Rémy and arrives in Auvers until his tragic end — the famous two months during which Johanna was close to him and during which he produced almost one painting a day.

• Johanna’s apprenticeship in the art world: from the day she inherited the works and opened the letters in 1891 until 1914, during which time she gradually manages to organise exhibitions and publish the correspondence between Vincent and Theo. 8 A disturbing conflict takes place between the man Johanna remembers and the artist she wants to bring to life in the eyes of the world. It suggests a tense narrative leading towards the possible interpretations of Van Gogh’s work at the time of his contemporaries and just after his death. And what if posterity only remembered him, as he wrote himself, as a “failure”? A sensitive, vulnerable and highly-strung person, as his brother described him? Or as the painter and writer of genius that she wanted to make known?

This film invites us to rediscover the work of Vincent Van Gogh through the character of Johanna Bonger Van Gogh, hissister-in-law and inheritor of his estate. Although she knew him only for the last two months of his life, she devoted her life to making his painting known to the world. By following her painstaking efforts to understand his art and make it known to critics and dealers, we see Van Gogh's genius in an unprecedented and profoundly human perspective.

Director's Statement:

Van Gogh'sfinal two months, which he spent in Auvers-sur-Oise, were one of the most prolific periodsin hislife. He painted more than 70 canvases at a frenetic pace, sometimes up to three a day. Striking masterpieces in thick strokes and contrasting colours, numerous Champs de Blé, Les Maisons à Gré, Le Jardin du Docteur Gachet, and ghost-like portraits: Docteur Gachet, Adeline Ravoux or Melle Gachet au Piano. It is also one of the most analyzed and commented-upon periods of his life, which ended in July when he shot himself in the chest,sealing hisfate as a doomed artist and feeding the legend of the mad painter that has generally taken hold ever since.

There is something that appeals to me about this fateful period in Auvers-sur-Oise and in the years that followed, unencumbered by subsequent debate. First, foremost and closest to the heart of the enigma, it concerns a woman who was a privileged witness to Vincent’s last months and who is none other than his own sister-in-law, Theo’s wife Johanna. She met Vincent just three times in his life: in Paris before he went to Auvers and then on two other occasions during the summer. She is nevertheless a central figure in the Van Gogh trio. She crossed paths with all the other protagonists who were close to him atthe time, such as Dr Gachet in Auvers. She saw friends of Vincent and Theo, such as the painters Émile 4 Bernard, Camille Pissarro, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the critic Albert Aurier, come and go in her apartment.

Above all, afterthe death of the two brothers, Vincent in July 1890 and Theo in January 1891, it was she who had the whole of Vincent's work before her eyes, even though it was considered almost worthless: it wasshe who took on the task of interpreting it, assembling it, curating it and bringing it to the attention of the critics and then the public. Widowed and a single mother at 27, she took up the study of art, almost in spite of herself, as it was neither her training nor her destiny. Despite the pain of her bereavement, she learned to recognise artists’ techniques with form and colour, and above all else to “love” Vincent, becoming his main posthumous champion.

In her notebooks, she hides nothing of her sadness, her difficulties in managing, or her difficulties in convincing her close friendsin the art world of Van Gogh’s genius. Naturally she makes a few blunders in naïvely asserting her convictions in a traditional world in which it would have been hard to imagine a widow having as much skill as her late husband. Sometimes she despairs, but never gives up. At night, when her child is asleep, she opens the voluminous correspondence between Theo and his brother, which he kept in a writing-desk and read over and over again before his death. She plunges in thinking she would rediscover Theo, the love of her life; instead she finds Vincent, the artist.

Her intuitive genius lay in understanding that the keys to Vincent’s work were to be found in these letters. After a few failed attemptsto convince the critics, Johanna began to charm them by reading passages from the correspondence. She managed to convince well-known friends and neighbours, including the painter Jan Veth and then the critic Roland Holst, who had initially been irritated by herincompetence. They changed their minds afterreading the letters and then helped her to mount a first exhibition in Amsterdam in 1892. On the strength of her experience, she then organized the great exhibition of 1905 at her own expense, the largest retrospective on Van Gogh in the history of art, which brought together some 500 works. Progressively, almost all over the world, she raised the price of Van Gogh’s paintings as well as interest in the artist: he was rediscovered as a genius who had been misunderstood during his lifetime.

So, thanks to Johanna, I can offer a new film on Van Gogh. As I see it, Johanna appears to be a key to the Van Gogh enigma: it was she — even, of course, if she was well-connected and supported — who was able to identify in Vincent what made him unique as an artist and to ensure his recognition. One could say that this is a feminine view of the famous artist that has never existed before, or that it is a kind of homage to a woman forgotten by history, but these are not the only reasons that legitimise the desire for this documentary today. To revisit Van Gogh’s biography and work through Johanna’s eyes and words is to tell the story of painting from the perspective of one who is not an art expert: to develop a naïve initial view and then a more sophisticated one, to embrace a form of apprenticeship of the vision by passing from letters to paintings and then from paintings to letters. It means finding Vincent through Johanna’s memories, through his relationship with his brother and the works he sent him, and finally through his own words: those of a man struggling with his demons and his art. In this way, perhaps, we get to (re)discover (the genius of) Vincent Van Gogh.

Synopsis:

The film is conceived as an intrigue around the interpretation of Van Gogh’s work. The narrative follows the last days of Vincent Van Gogh — two months — and his legacy. The plot is set out from the beginning of the film by focusing on the character of Johanna. From the outset, she is alone as Theo’s widow, surrounded by Vincent’s paintings and the letters between the two brothers. From this situation, I build a scenario that plays with flashbacks, a natural element in a period of mourning. With no idea of what to do but take over her husband’s mission, calling up her memories, distraught when she is advised to burn the paintings as “the work of a madman”, Johanna takes the letters from the famous writing-desk. The more she reads, the more memories of Vincent, through Theo, come back to her. I imagine her looking at the paintings around her, contemplating them, perhaps even lost in speculation about his troubled personality, his incomparable talents, his energy in producing so many paintings, or about what might have happened at the end of his life. From the paintings,she turnsto words, to letters. There she finds a new key, new clues, new memories. She returns to the paintings. Slowly, Vincent the artist is revealed to her, and she becomes his ardent champion for the rest of her life. I imagine this scene being played out in the film in the villa in Bussum, then in the house in Amsterdam, where again and again she positions Vincent’s paintings more or less as they had been in the conjugal apartment in Pigalle. This scene emphasizesJohanna’s concerns about the immensity of Vincent’s œuvre, which is always present, confronting her.

Meanwhile, the film progresses through two narrative threads in two different time spaces:

• Vincent at work: from the moment he leaves the asylum in Saint Rémy and arrives in Auvers until his tragic end — the famous two months during which Johanna was close to him and during which he produced almost one painting a day.

• Johanna’s apprenticeship in the art world: from the day she inherited the works and opened the letters in 1891 until 1914, during which time she gradually manages to organise exhibitions and publish the correspondence between Vincent and Theo. 8 A disturbing conflict takes place between the man Johanna remembers and the artist she wants to bring to life in the eyes of the world. It suggests a tense narrative leading towards the possible interpretations of Van Gogh’s work at the time of his contemporaries and just after his death. And what if posterity only remembered him, as he wrote himself, as a “failure”? A sensitive, vulnerable and highly-strung person, as his brother described him? Or as the painter and writer of genius that she wanted to make known?

Awards

Shanghai International TV Festival – Nominee Award Magnolia (Best Documentary)

2023, France, 53 min.

documentary, biography, art

Language: French, Russian subtitles

18+

Schedule

There are no screenings in your city currently..